Read through these two explanations, and note which one appeals to you more.

SPI – Take One

“The schedule performance index (SPI) is a measure of schedule efficiency expressed as the ratio of earned value to planned value. It measures how efficiently the project team is using its time. It is sometimes used in conjunction with the cost performance index (CPI) to forecast the final project completion estimates…The SPI is equal to the ratio of the EV to the PV. Equation: SPI = EV/PV.” – A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide) – Fifth Edition, p.219

SPI – Take Two

Don manages projects, meaning he’s responsible for making sure the work to produce a product or service is broken into manageable chunks, and completed when it was planned to complete. Don’s boss, the one whose budget the project work cost is coming from, asks for regular updates on the progress of the project. Don’s boss, understandably, does not like surprises! If Don looks at how much work has been competed at any given time versus how much work was planned to have been completed, he can calculate what we call Schedule Performance Index, or SPI. If Don looks at how much money has been spent to get the work done versus how much money was planned to be spent at some point in the project, he can calculate Cost Performance Index, or CPI. Together, SPI and CPI can give you an idea if your project will get done when you said it would, and if it’s going to come in on, under, or over budget. Don’s boss really appreciates these project metrics.

Explanation Problem

In the book The Art of Explanation: Making Your Ideas, Products, and Services Easier to Understand, by Lee LeFever, the author states that there is a kind of problem that is so common we don’t even realize it’s there. This is “the explanation problem”.

An explanation problem is related to how we choose to communicate ideas. What makes an explanation problem so insidious is that it has the power to ruin the best, most productive, life changing ideas in just a few sentences.

The Art of Explanation

Lee Lefever

Bummer.

The Curse of Knowledge

I first came across the term ‘curse of knowledge’ in the book The Art of Explanation. Essentially the Curse of Knowledge states that once you know something, it’s really difficult to remember not knowing it. In other words, it’s difficult to put yourself in the state of mind of someone who doesn’t know the thing you now know.

As engineers, scientists, and technical folks we often have to and want to present our ideas to management, or to non-technical people. We need to recognize that we are afflicted with the Curse of Knowledge. Everyone is. But if we can recognize it, we can work to overcome it. Marry that with a story-telling outline, and with a little bit of prep, we can make our explanations better understood.

The Continuum of Knowledge

Both of the explanations presented explain SPI, or Schedule Performance Index. This is a common project management metric used to understand how the project is actually doing versus planned. But one of them takes into consideration the Curse of Knowledge and the other one does not.

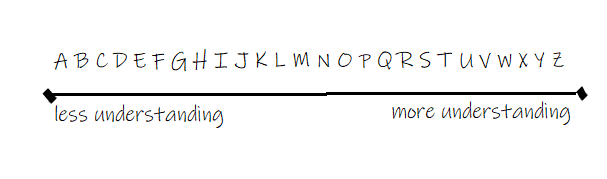

LeFever uses a continuum of A to Z to illustrate what we need to consider when explaining.

Most of the time, when you are explaining something, you are near the “end” of the alphabet. Maybe you are at W, X, Y or Z. If the people you are explaining it to do similar work but just haven’t heard the concept before, maybe they are at an S or T level. But your boss might be in the middle, maybe an M. And non-technical people may be at an A, B, or C level.

If we take into consideration where people might be on the knowledge continuum (part of seeking to understand), you can then tailor your explanation to include as much background and context as needed for them to feel comfortable with your explanation and understand what you are trying to communicate.

In our example, I tailored the explanation to people who might not quite understand what a project manager does. Did it help that I spent a sentence on what a project manager does, and another couple on why we would want to measure anything (i.e. so we can report to the person who is responsible for the budget)? To be fair, in the first example, the PMBOK Guide does spend a lot of time defining what a project manager does, just not in one sentence. But to read the entire PMBOK guide (the 5th edition is 567 pages with the glossary) is not practical nor needed in our explanation of SPI.

Tell Me a Story

The other technique used in the second explanation was storytelling. LeFever illustrates the format this way:

- Meet Bob; he’s like you

- Bob has a problem that makes him feel bad

- Now Bob found a solution, and he feels good!

- Don’t you want to feel like Bob?

Storytelling isn’t always the right way to go. For example, if you are communicating the specifications of a microprocessor to me, I don’t need you to tell me a story. Also, as LeFever points out, if you are short on time then storytelling might not be the way to go either. It takes a bit more time to tell a story, so if you are constrained by time you may choose a more direct communication approach.

tl;dr

Before you explain something, plan your communication. Remember the Curse of Knowledge (it’s difficult to remember not knowing the thing you are explaining) and consider the knowledge level of the audience and tailor your presentation. Give context or background information as needed. If appropriate, tell a story instead of directly communicating the information.

engineer your life

- Consider the question, “What do you do for a living?” Tailor an answer to someone at the A or B level on the knowledge continuum. [Before I read this book I resorted to “I work with computers.” Now I can give a better answer!]

- Read the book, The Art of Explanation: Making Your Ideas, Products, and Services Easier to Understand, by Lee LeFever.